Hi, nerd blog. I’m not a person who cares much about privacy (which makes the fact that I’m currently a PhD student studying cryptography a little weird). But, there are some relatively basic levels of privacy that I think people are clearly entitled to.

For example, suppose that I want to know whether or not someone has an account on a certain website, and I don’t think he’d want to tell me. It’s not hard to imagine an example where that information could be harmful. The site might be for online dating or porn, or it might be somehow related to a counterculture, a protest movement, etc. The person might be someone that I’m angry at, a romantic interest, someone that I’m considering hiring, an ex, etc. Anyone who’s gone to middle school should recognize that people will certainly look for this information if they know where to find it.

It turns out that on many websites, you can do this–including extremely large websites. I’ll use economist.com as my first example because it’s a non-embarrassing website that I have an account on that has this flaw, as shown below.

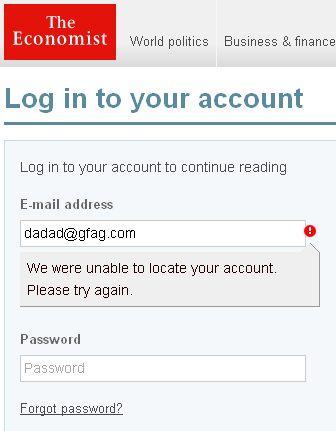

Here’s what happens when you try to log in to economist.com with a gibberish e-mail address:

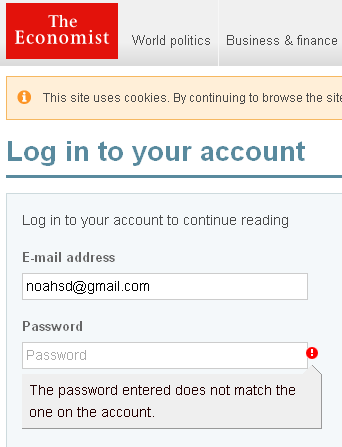

Here’s what happens when I use my e-mail address and gibberish for a password:

So, you now all know that I have an account on this website, and if I want to know whether or not someone else does, all I need is her e-mail address.

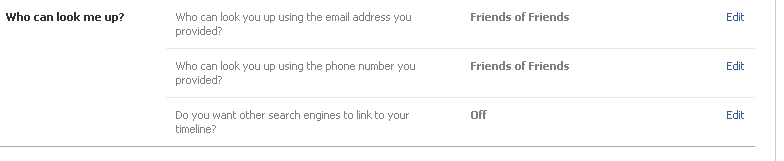

Facebook also makes this mistake. Here are my Facebook privacy settings, in which I quite unambiguously say that you should need to be friends with one of my friends to find my Facebook account using my e-mail address:

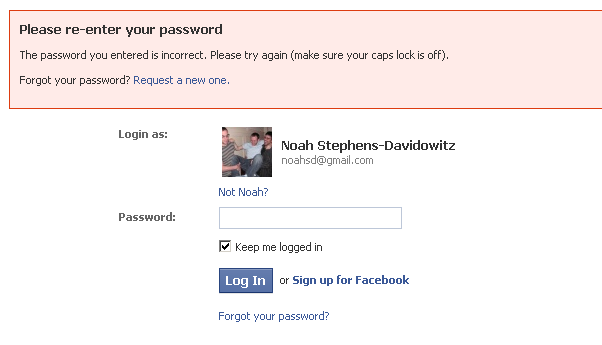

Here’s what happens when you simply enter my e-mail address into Facebook’s login with a gibberish password:

On Facebook, this actually also works with phone numbers, and either way, they conveniently show an image of me and my name, in addition to verifying that I have an account.

Now, that’s just stupid, and it shouldn’t happen. The way to fix this is incredibly obvious: On a failed login, just say “Sorry, that e-mail/password combination is wrong.” instead of telling users specifically which credential is wrong. This has been accepted best practice for a long time, and it’s amazing to see such large companies screw it up. However, it’s hard not to roll your eyes because, well, most people would not be embarrassed if someone who already had their e-mail address also knew whether or not they subscribed to The Economist or have a Facebook account.

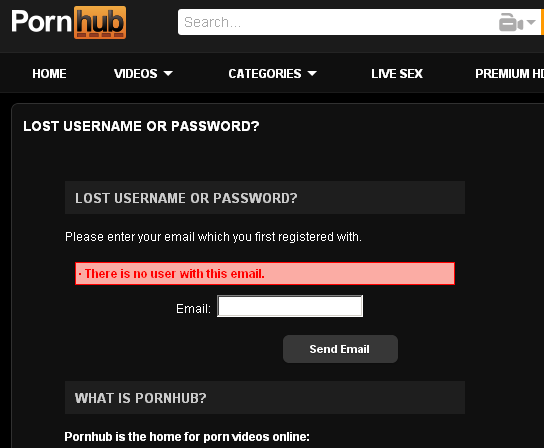

So, let’s pick something more sensitive. Say, for example, pornography. According to Wikipedia, Pornhub is one of the largest porn sites, and the 81st most popular website on the entire internet according to Alexa rankings (which likely undercounts such sites). It’s fairly obvious why someone wouldn’t want anyone with his e-mail address to know whether or not he has a Pornhub account. While Pornhub does not fall to the exact attack that I describe, it’s a nice example of a slightly different attack that accomplishes the same thing. Here’s what happens when you enter an invalid e-mail address into Pornhub’s “Forgot your password” page:

So, want to know whether or not someone has a Pornhub account? Go to the website, click “Forgot your password,” and enter his e-mail address. (Of course, if he does have an account, he’ll get an e-mail. He might ignore it, but if he’s aware of this attack, he might recognize that someone did this to him. He won’t know who, though, and you’ll still have the information.)

In spite of the fact that this has been known for a long time, I’m willing to bet that the second attack works on the vast majority of sites on the web. I’ll spare more screenshots and naming-and-shaming, but a quick check shows that it works on lots of other porn sites, lots of dating sites, lots of online forums about sensitive topics, sites for companies devoted to web security, and, in general, just about every site I checked. (Sometimes, you have to use the “Forgot your username” link instead of “Forgot your password.”)

The solution? Obviously, just say “If you’ve entered the correct address, you will receive an e-mail shortly. If you don’t, please try a different address.” Fortunately, one site that screwed a lot of stuff up actually got this right: Healthcare.gov.