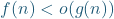

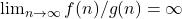

(Summary: I propose that we should use inequalities with asymptotic notation like big-![]() , big-

, big-![]() , little-

, little-![]() , little-

, little-![]() , and

, and ![]() when they represent only an upper bound or only a lower bound. E.g.,

when they represent only an upper bound or only a lower bound. E.g., ![]() or

or ![]() or

or ![]() .)

.)

Recall the big-![]() asymptotic notation. E.g., for two functions

asymptotic notation. E.g., for two functions ![]() , we write

, we write ![]() to mean that there is some universal constant

to mean that there is some universal constant ![]() such that

such that ![]() . (Of course, there are many many variants of this. I tried here to choose a setting—functions whose domain is the positive integers and range is the positive reals—in which this notoriously ambiguous notation is least ambiguous. But, everything that I will say about big-

. (Of course, there are many many variants of this. I tried here to choose a setting—functions whose domain is the positive integers and range is the positive reals—in which this notoriously ambiguous notation is least ambiguous. But, everything that I will say about big-![]() notation below has exceptions. Indeed, any attempt to formally define how this notation is actually used in any reasonable amount of generality will quickly fail in the face of our collective notational creativity.) For example,

notation below has exceptions. Indeed, any attempt to formally define how this notation is actually used in any reasonable amount of generality will quickly fail in the face of our collective notational creativity.) For example, ![]() and also

and also ![]() , but

, but ![]() and

and ![]() . As a more complicated and mildly interesting example, we have

. As a more complicated and mildly interesting example, we have ![]() but

but ![]() . (Proving the latter fact requires a tiny bit of diophantine approximation.)

. (Proving the latter fact requires a tiny bit of diophantine approximation.)

To greatly understate things, this notation is useful. But, a common complaint about it is that it is an abuse of the equals sign. (Deligne points out that the equals sign is actually abused quite frequently.) Indeed, it is a little disconcerting that we write an “equality” of the form ![]() when the left-hand side and the right-hand side don’t even seem to have the same type. (What even is the type of the right-hand side

when the left-hand side and the right-hand side don’t even seem to have the same type. (What even is the type of the right-hand side ![]() ? The left-hand side is clearly a function of a variable

? The left-hand side is clearly a function of a variable ![]() . The right-hand side clearly is not a function of

. The right-hand side clearly is not a function of ![]() , since it makes no sense to ask what its value is at, say,

, since it makes no sense to ask what its value is at, say, ![]() .) And, it is quite worrisome that this use of the equals sign is not at all symmetric, since

.) And, it is quite worrisome that this use of the equals sign is not at all symmetric, since ![]() certainly does not imply that

certainly does not imply that ![]() (and we would never write

(and we would never write ![]() ).

).

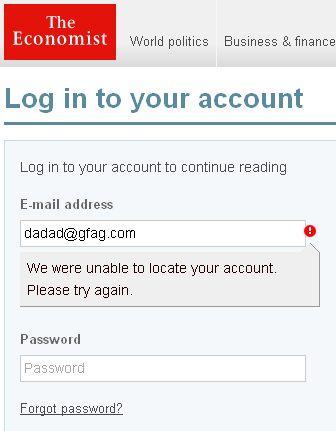

These problems are of course confusing for people when they first encounter the notation. But, they also lead to many little annoying issues in actual papers, where even brilliant computer scientists and mathematicians will frequently write silly things like “we prove a lower bound of ![]() on the running time of any algorithm for this problem.” This is presumably meant to suggest that the lower bound is good in that it is reasonably large (presumably that it grows quadratically with

on the running time of any algorithm for this problem.” This is presumably meant to suggest that the lower bound is good in that it is reasonably large (presumably that it grows quadratically with ![]() ) but when interpreted literally, this statement suggests that the authors have proven some unspecified lower bound

) but when interpreted literally, this statement suggests that the authors have proven some unspecified lower bound ![]() satisfying

satisfying ![]() . For example, a lower bound of

. For example, a lower bound of ![]() on the running time of an algorithm is almost never impressive but certainly satisfies this. (In such cases, the authors usually mean to say “we prove a lower bound of

on the running time of an algorithm is almost never impressive but certainly satisfies this. (In such cases, the authors usually mean to say “we prove a lower bound of ![]() .”)

.”)

Of course, this is really just pedantry, since in almost all such cases it is perfectly clear what the authors meant. But, (1) pedantry is good; (2) saying “what I wrote is technically wrong but the reader should be able to figure it out” is rarely good; and (3) in even slightly more complicated or less clear cases, this can and does lead to confusion or even bugs.

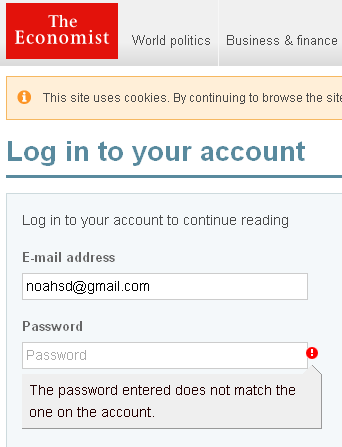

A commonly proposed resolution to this is to interpret ![]() as the set of all functions such that

as the set of all functions such that ![]() is bounded. Then, rather than writing

is bounded. Then, rather than writing ![]() , one should write

, one should write ![]() . A lot of people like to point out that this is technically more accurate (see Wikipedia), and one occasionally sees such notation used in the wild. However, it is used quite rarely, in spite of the fact that people have been pointing out for decades that this is the “technically correct notation.” I won’t pretend to truly know how other people’s minds work, but I suspect that the reason that this notation has not caught on is simply because it does not match how we think about big-

. A lot of people like to point out that this is technically more accurate (see Wikipedia), and one occasionally sees such notation used in the wild. However, it is used quite rarely, in spite of the fact that people have been pointing out for decades that this is the “technically correct notation.” I won’t pretend to truly know how other people’s minds work, but I suspect that the reason that this notation has not caught on is simply because it does not match how we think about big-![]() . I don’t think of

. I don’t think of ![]() as meaning “

as meaning “![]() is in the set of functions such that…”, but instead, I think of it as representing an upper bound on

is in the set of functions such that…”, but instead, I think of it as representing an upper bound on ![]() . (Of course, more-or-less any mathematical notation can be defined in terms of sets, and in many formal axiomatizations of mathematics, everything simply is a set. E.g., an overly formal interpretation of the notation

. (Of course, more-or-less any mathematical notation can be defined in terms of sets, and in many formal axiomatizations of mathematics, everything simply is a set. E.g., an overly formal interpretation of the notation ![]() is really saying that the ordered pair

is really saying that the ordered pair ![]() is contained in the set of ordered pairs defining the relation

is contained in the set of ordered pairs defining the relation ![]() . But, we do not parse it that way in most situations. So, the fact that it is technically consistent to view the statement

. But, we do not parse it that way in most situations. So, the fact that it is technically consistent to view the statement ![]() as placing

as placing ![]() in a set is not very interesting. The question is really whether it’s actually convenient to view the notation in this way.)

in a set is not very interesting. The question is really whether it’s actually convenient to view the notation in this way.)

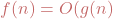

So, I propose that we use inequalities with big-![]() notation in this context. For example, I propose that we write

notation in this context. For example, I propose that we write ![]() . To me, this simply represents exactly what is meant by the notation. Indeed, it is difficult for me to read

. To me, this simply represents exactly what is meant by the notation. Indeed, it is difficult for me to read ![]() and interpret it in any way other than the correct way. Specifically, it represents an asymptotic upper bound on

and interpret it in any way other than the correct way. Specifically, it represents an asymptotic upper bound on ![]() in terms of

in terms of ![]() . (Here and throughout, I am using blue to represent the notation that I am proposing and red to represent the more standard notation.)

. (Here and throughout, I am using blue to represent the notation that I am proposing and red to represent the more standard notation.)

In fact, I find that this notation is so intuitive that in my papers and courses, readers immediately know what it means without me even having to mention that I have switched from the more conventional ![]() to the variant

to the variant ![]() . (This is why I view this as a quite “modest” proposal.) One can therefore simply start using it in ones work without any fanfare (or any apparent downside whatsoever)—and I suggest that you do so.

. (This is why I view this as a quite “modest” proposal.) One can therefore simply start using it in ones work without any fanfare (or any apparent downside whatsoever)—and I suggest that you do so.

More generally, when asymptotic notation is used to represent an upper bound, we should write it as an upper bound. Anyway, that’s the high-level idea. I’ll now go into more detail, explaining how I think we should write more complicated expressions with asymptotic notation and how to use the same notation in the context of big-![]() , little-

, little-![]() , little-

, little-![]() , big-

, big-![]() , and

, and ![]() . To be clear, this idea is not novel, and one can already find it in many papers by many excellent authors. It seems that most authors mix inequalities and equalities rather freely in this context. (I asked ChatGPT to find early examples of this notation, and it found a 1953 paper by Tsuji, where he uses this notation in chains of inequalities. More generally, this notation is more often used in the literature in chains of inequalities and in other spots where inequalities might seem more natural than equalities.) I am merely advocating that we as a community try to use it consistently—in papers and in teaching.

. To be clear, this idea is not novel, and one can already find it in many papers by many excellent authors. It seems that most authors mix inequalities and equalities rather freely in this context. (I asked ChatGPT to find early examples of this notation, and it found a 1953 paper by Tsuji, where he uses this notation in chains of inequalities. More generally, this notation is more often used in the literature in chains of inequalities and in other spots where inequalities might seem more natural than equalities.) I am merely advocating that we as a community try to use it consistently—in papers and in teaching.

Fancier use cases and choosing the direction of the inequality

Of course, big-![]() notation gets used in fancier ways than simply writing things like

notation gets used in fancier ways than simply writing things like ![]() . For example, one might wish to say that an event happens with probability that is at least

. For example, one might wish to say that an event happens with probability that is at least ![]() for some constant

for some constant ![]() , which many will write quite succinctly as

, which many will write quite succinctly as ![]() . Now the big-

. Now the big-![]() has made its way all the way up to the exponent! And, because of the minus sign, this is actually a lower bound on

has made its way all the way up to the exponent! And, because of the minus sign, this is actually a lower bound on ![]() using big-

using big-![]() notation, whereas simpler uses of big-

notation, whereas simpler uses of big-![]() always yield upper bounds.

always yield upper bounds.

In this case, I naturally propose writing ![]() . This again makes it very clear what’s going on—we are giving a lower bound on

. This again makes it very clear what’s going on—we are giving a lower bound on ![]() .

.

One might have a more complicated expression such as ![]() or something, where it is quite easy to get confused about whether an upper bound or lower bound on

or something, where it is quite easy to get confused about whether an upper bound or lower bound on ![]() is intended. (Yes, I know that this expression simplifies.) In these cases, using an inequality sign provides some help to the reader, as evidenced by how much easier it is (at least for me) to parse the expression

is intended. (Yes, I know that this expression simplifies.) In these cases, using an inequality sign provides some help to the reader, as evidenced by how much easier it is (at least for me) to parse the expression ![]() . So, one does a real service for the reader by writing

. So, one does a real service for the reader by writing ![]() .

.

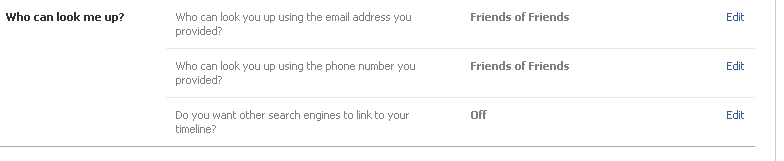

There are also examples where the traditional notation is actually formally ambiguous. This often occurs when big-![]() is used around a lower-order term, such as in the expression

is used around a lower-order term, such as in the expression ![]() . Here, it is not clear whether one simply means that

. Here, it is not clear whether one simply means that ![]() for some constant

for some constant ![]() , or if one means that

, or if one means that ![]() for some constant

for some constant ![]() . (A formal reading of the definition of big-

. (A formal reading of the definition of big-![]() would suggest the former, but I think authors typically mean the latter. Admittedly, some of the ambiguity here comes from the question of how big-

would suggest the former, but I think authors typically mean the latter. Admittedly, some of the ambiguity here comes from the question of how big-![]() interacts with functions taking negative values, which I am deliberately ignoring.) Here, the notation that I am proposing can help a bit, in that one can write

interacts with functions taking negative values, which I am deliberately ignoring.) Here, the notation that I am proposing can help a bit, in that one can write ![]() in the first case while still writing

in the first case while still writing ![]() in the second case. (Of course, unless this notation comes into very widespread use, one should not assume that the reader recognizes the distinction. One should often clarify in more than one way what one means in cases where the risk of ambiguity is great. When it doesn’t matter much—e.g., in an aside, or in a case where the weaker fact

in the second case. (Of course, unless this notation comes into very widespread use, one should not assume that the reader recognizes the distinction. One should often clarify in more than one way what one means in cases where the risk of ambiguity is great. When it doesn’t matter much—e.g., in an aside, or in a case where the weaker fact ![]() is all that’s needed but the stronger fact that

is all that’s needed but the stronger fact that ![]() is true—one can simply rely on this notation to suggest the correct interpretation without burdening the reader with much discussion.) In particular, notice that if one truly means that

is true—one can simply rely on this notation to suggest the correct interpretation without burdening the reader with much discussion.) In particular, notice that if one truly means that ![]() , then the use of the equals sign in the expression

, then the use of the equals sign in the expression ![]() is actually justified, since we are in fact placing

is actually justified, since we are in fact placing ![]() in an equivalence class in this case (whereas the notation

in an equivalence class in this case (whereas the notation ![]() does not place

does not place ![]() in any reasonable equivalence class). We will see more examples of this below

in any reasonable equivalence class). We will see more examples of this below

All of this means that authors who use this convention must be sure to carefully think about what specifically they mean when they write asymptotic notation. That is a good thing.

Cousins of big-

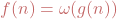

Big-![]() also has its close cousins big-

also has its close cousins big-![]() , little-

, little-![]() and little-

and little-![]() , and it is relatively straightforward to see how these notations should be modified.

, and it is relatively straightforward to see how these notations should be modified.

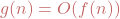

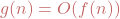

- Big-

the old way: One typically writes

the old way: One typically writes  if and only if there is some universal constant

if and only if there is some universal constant  such that

such that  . Equivalently,

. Equivalently,  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

My recommendation: As you might guess, I recommend instead writing , to make clear that the big-

, to make clear that the big- notation is giving a lower bound.

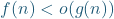

notation is giving a lower bound. - Little-

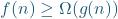

the old way: One typically writes

the old way: One typically writes  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

My recommendation: I recommend instead writing . This makes clear both that the little-

. This makes clear both that the little- notation is giving an upper bound, and in my opinion the strict inequality does a good job of representing the distinction between big-

notation is giving an upper bound, and in my opinion the strict inequality does a good job of representing the distinction between big- and little-

and little- . In particular,

. In particular,  means that

means that  is “asymptotically strictly smaller” than

is “asymptotically strictly smaller” than  , where the fact that this inequality is strict is justified formally by the fact that

, where the fact that this inequality is strict is justified formally by the fact that  .

. - Little-

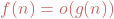

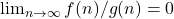

the old way: One typically writes

the old way: One typically writes  if and only if

if and only if  . Equivalently,

. Equivalently,  if and only if

if and only if  .

.

My recommendation: As you might guess, I recommend instead writing .

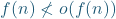

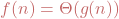

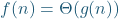

. - Big-

the old way: One typically writes

the old way: One typically writes  if and only if

if and only if  AND

AND  .

.

My recommendation: Keep doing it the old way! When we write , we are in fact proving both an upper and lower bound on

, we are in fact proving both an upper and lower bound on  and we are relating

and we are relating  and

and  according to an equivalence relation. So, in this case, the traditional notation is already great!

according to an equivalence relation. So, in this case, the traditional notation is already great!

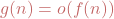

As before, in slightly more complicated expressions the inequality sign can flip. E.g., ![]() is a perfectly good lower bound in terms of little-

is a perfectly good lower bound in terms of little-![]() , just like

, just like ![]() is a lower bound in terms of big-

is a lower bound in terms of big-![]() and

and ![]() is an upper bound in terms of little-

is an upper bound in terms of little-![]() . And, sometimes the specific choice of which (in)equality symbol to use can convey additional meaning that is not clear without it, like in the expression

. And, sometimes the specific choice of which (in)equality symbol to use can convey additional meaning that is not clear without it, like in the expression ![]() , where the inequality is meant to make clear that an upper bound on

, where the inequality is meant to make clear that an upper bound on ![]() is all that is intended. In contrast,

is all that is intended. In contrast, ![]() suggests that we also mean that

suggests that we also mean that ![]() .

.

I’ll end by noting that big-![]() notation has some rather distant cousins for which this notation is particularly important. For example, there is the

notation has some rather distant cousins for which this notation is particularly important. For example, there is the ![]() notation, where one writes

notation, where one writes ![]() to mean… something. In fact, out of context, it is often entirely unclear what this notation means. This might mean that

to mean… something. In fact, out of context, it is often entirely unclear what this notation means. This might mean that ![]() for some constant

for some constant ![]() , or it might mean

, or it might mean ![]() for some constant

for some constant ![]() , or it might mean that both things are true. (Note that including the constant

, or it might mean that both things are true. (Note that including the constant ![]() in two places is a convenient trick to avoid needing two constants.) Of course, often the context makes this clear. But, one can be unambiguous by instead writing

in two places is a convenient trick to avoid needing two constants.) Of course, often the context makes this clear. But, one can be unambiguous by instead writing ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() respectively. Other examples of distant cousins include

respectively. Other examples of distant cousins include ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , etc. For example, one traditionally writes

, etc. For example, one traditionally writes ![]() to mean that

to mean that ![]() , i.e., that

, i.e., that ![]() is a negligible function. Hopefully it is clear to the reader what I propose: we should write

is a negligible function. Hopefully it is clear to the reader what I propose: we should write ![]() .

.

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\sigma_1^{(n-1)} = \begin{cases}\pi^{n/2} \cdot \frac{2}{(n/2-1)!} &n\text{ even}\\\pi^{(n-1)/2} \cdot \frac{2^n \cdot ((n-1)/2)!}{(n-1)!} &n\text{ odd}.\end{cases}\]](http://www.solipsistslog.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-7093395acfb9701717087f97c5b73145_l3.png)